|

Washington’s Birthday

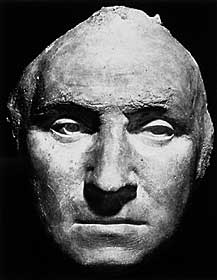

Happy Birthday, G. Washington! This Sunday we celebrate the 272nd birthday of the man who is justly known—though so few have an adequate understanding why—as the Father of our Country. That the Father of the United States of America was one of the greatest men who ever lived, who impressed on this country his character, his prudence and far-seeing political wisdom, his extraordinary personal force modulated by his mildness and self-control, his dedication to classical ideals of honor and patriotism combined with his future-oriented grasp of an expanding America, his profoundly felt sense of America’s reliance on the protection and guidance of Divine Providence (and not just Providence, but Jesus Christ, as can be seen in his 1789 proclamation of a national day of thanksgiving), and his deeply experienced vision of the national Union, is something that we are still receiving the benefits of to this day, in myriad and incalculable ways, even in the midst of our current decadence, and even if we ourselves don’t know it and don’t care. We are so accustomed to the Gilbert Stuart portraits, painted in Washington’s sixties when he was already showing premature signs of age (though his firmness of character was not diminished), that it can be a shock to see a more vital Washington. Here is a marvelously life-like image of the then 53-year-old Washington rarely seen by Americans, one of the heads sculpted by Jean Antoine Houdon from the life mask he cast when he visited Mount Vernon in 1785, now at the Museum of the Louvre in Paris. Houdon told a friend he was in awe of “the majesty and grandeur of Washington’s form and features.” One has the same awe at Houdon’s genius; it is to be doubted that any photograph could make us feel that we are as close to the living man as he really was:

Here is another head made by Houdon from the same life-mask, enabling us to look directly into Washington’s face as though he were standing before us:

In the moving final verse of Byron’s “Ode to Napolean Bonaparte,” the poet turns away in disgust from that vain French tyrant and looks westward to find a man who embodies true political virtue:

Where may the wearied eye repose Posted by Lawrence Auster at February 20, 2004 10:51 AM | Send Comments

Excellent blog-entry! Thank you, Mr. Auster. The scuptures are indeed astonishing to behold. Posted by: Paul Cella on February 20, 2004 12:37 PMHonestly, when you reflect on how the formation of the United States of America altered the course of human history and its values, it give me goose bumps whenever I read about Washington. The intellectual and moral clarity of his generation still reverberates down to our time. There’s just something about him and his peers that gives you a sense of pride in the human spirit that is energizing, for the first time in history we had representative institutions based on the authenticity of individual freedom and liberty, not enslavement to the will of the state. What a tragedy if we slide back to it. They never said it would be perfect, but if can anyone think of something better to bring so much wealth and opportunity to ordinary people bring it on; just try and get ahead in Europe today, they’re still operating in medieval mode. The aristocrats are now called “planners” or “experts” and they always end up with everything in their own pockets. Anyone used European designed software or computers recently? What about an invention from there since 1950? Posted by: sons_of_freedom on February 20, 2004 2:49 PMThe character of General Washington was the wonder of the world in his day. The fact that he refused a crown when offered — practically demanded of him — sent shockwaves through monarchical Europe. The Sword of Washington won our independence. His firm and steady hand guided our Republic through her early years. The United States have one to their credit that no other people can boast of! To think of what it meant during that Second Continental Congress, where he worn his military attire to symbolize the willingness of Virginia to take up arms against tyranny. Fate left him the only man present in uniform. When Mr. Adams began to make a speech recommending a man whose identity became clearer with each phrase, Washington retreated embarrassed to the library and knew not what occurred until other members came out and began addressing him as “General.” And what if the Congress had second thoughts later about taking on the great world power of Britain and went home? There he would have stood, the most conspicuous of traitors in the Mother Country’s eye. What a relief it must have been, after a year on the field of battle, to receive word of the unanimous Declaration of Independence, all the States now behind him, no turning back win or lose! Perhaps an even greater achievement than leading our great Revolution was establishing the precedent of an orderly and peaceful, non-hereditary transfer of power, as John Adams succeeded him as President. Many thought such a phenomenon could not happen. And I’ll stop here. Posted by: Joel LeFevre on February 20, 2004 9:57 PMOn the idea of the exposed position Washington was in during the Revolution, and how he became the rallying symbol of America: At the moment when he was appointed commander of the Continental Army, he was its only member. We could talk a lot about the role of fate in Washington’s career, and its amazing coherence. As a 22-year-old officer in the back woods of western Pennsylvania, he ordered the first shot fired in what became the French and Indian War, which led to the struggle between Great Britain and the Colonies which led to the Revolutionary War. So, as fate had it, he personally lit the spark that led ultimately to independence and nationhood. For the eight and a half years of the War of Independence, he struggled to hold an army in existence without sufficient government support, money, or men. That miserable experience burned into his brain what it was like to live under a government that doesn’t have the power or energy to act. As a result, he, probably more than any other man in America, understood the importance of having a government with real sovereignty and real unity and the ability to defend itself and enforce its own laws. That was what he urged in his circular letter to the states when he stepped down as general. Then, when the disfunctional nature of the Articles of Confederation became more and more unacceptable during the 1780s, he was the prime force pushing for a real government for the United States. And so he became the president of the Constitutional Convention, and then President of the United States. During his second term in the Presidency, the terrible conflict emerged (which seventy years later ultimately turned into the Civil War) between the Jeffersonians who thought the U.S. government was simply the agent of the states, and the Washingtonians who saw the government as having sovereign power (limited, of course, by the federal structure and by checks and balances). For holding to that position, the once-universally beloved Washington was made into an object of suspicion, paranoia and contempt by the Jeffersonians, much as conservatives today are treated by liberals. The theme of his Farewell Address in 1796 was the unity of the United States, the need to have devotion and love to the Union. He was saying this at a time when the Union he was describing so eloquently didn’t yet quite exist. Yet that sense of the Union, of the importance of the Union, and of love for the Union, was something he felt in every cell of his body. It was the result of his entire life’s experience. He embodied it, and others followed him, and the result was the United States of America. Posted by: Lawrence Auster on February 20, 2004 10:34 PMIf anyone wants to enhance the large image of Washington above, right-click on it, click Copy, and then paste it into MS Word. The result will be larger than the image here and even more vivid and life-like. Posted by: Lawrence Auster on February 20, 2004 11:33 PMMagnificent is Washington’s sculpture which, because of the artistry, is perhaps the most genuine reflection of this extraordinary human being. The artist interacts with the subject and has insights into the subject’s character. The mask removes the possibility of exaggeration by the artist. Napoleon and Julius Caesar; I can’t think their representations are the equal of Washington’s. But then I am an American, not a Frenchman or a Roman. Posted by: P Murgos on February 20, 2004 11:35 PMA very inspiring post! Unlike most of the presidents we revere (for good or ill) today, Washington was already viewed as Olympian during his lifetime. He was so lofty it’s hard to imagine him down among the common folks. Late last summer I was fortunate to be afforded a glimpse of what that might have been like. A letter written in 1875 claimed my 4th-great-granduncle served Washington as a “foot page” when he was 11. I long dismissed this as poppycock; family stories tend to inflate over 97 years. But last summer I learned the boy’s grandfather had a farm in a hamlet where, what do you know, Gen. Washington and his Army arrived that year, commandeered a merchant’s house and a Quaker meetinghouse, and stayed for two months. Now the story seems plausible, if unprovable. In September this town put on a commemorative 225th-anniversary reenactment, which I made the 1,000-mile trek to see. Now, mind you, nothing much happened during this period. It was a dull stretch in the war. Other than odd Tory raids on nearby farms, there was no action to speak of locally. The General sat at a desk most mornings and wrote correspondence. He occasionally visited nearby allies. The high point of the two months was an oxroast for the first anniversary of the victory at Saratoga. But, boy, if the whole town didn’t come out for this event! Of course, there was a bit more pageantry in 2003 than in 1778, what with the General (or a credible facsimile thereof) riding in through a sea of flags to read a proclamation on the porch. The house and yard are well-preserved, and it was awe-inspiring to stand in the humble room where he wrote those daily letters. Indeed, the lack of drama was an advantage, as it allowed us to watch the prosaic tasks of the day done without distraction. Whatever these kids are fed in the schools during the week, they got none of it on the weekend. There wasn’t an ounce of correctness or revisionism to be seen anywhere. But, as with any good reenactment, all sides were represented— Continentals, militiamen, Loyalists, Brits, Hessians, Indians— and treated with respect. I think the townschildren are safe for another few years. (“He was in our town!”) Sorry to have gone on like this. If you’d like to know where the General was on any given day during the war, here is a handy chart: Thanks to Caesar for the Washington itinerary. A terrific resource. Now according to Flexner’s biography, Washington resided in 280 different headquarters during the 8 1/2 years he commanded the Continental army. The list you’ve provided has 360 lines. I supposed the difference might be accounted for by the fact that some of the items might be places where he stayed briefly but that were not designated as headquarters. Between June 23, 1775 and December 24, 1783 (he arrived back at Mount Vernon on Christmas eve), there are 3,106 days. 3106 divided by 360 is 8.6. So Washington changed his residence on the average of once every 8 1/2 days for 8 1/2 years. However, I see that many items on the list show Washington as arriving and leaving on the same day. So perhaps the list includes inns and homes where he merely ate or rested for a few hours rather than spent the night. So maybe Flexner’s figure of 280 different residences is correct after all, in which case Washington changed residence on an average of once every 11 days during those 8 1/2 years. During that vast period of time he spent two nights at his home at Mount Vernon, after the victory over Cornwallis. Other than Alexander the Great and his men, I wonder if any soldier was away from his home for so long, almost continually on the move? Posted by: Lawrence Auster on February 21, 2004 2:16 AMHow incomparably blessed is this nation to have such a man as its father! The more I read about George Washington, the more I am impressed. All Americans would do well to study his writings and remarks, along with those of his contemporaries. Washington is truly worthy of the traditional appelation - the father of our nation. May the people of this nation turn from their blindness and wickedness so that the true greatness of this man will be once again be celebrated, and his name will be honored from the concrete canyons of New York city to the sandstone canyons of the West. Posted by: Carl on February 22, 2004 2:16 AM |