|

How I came to write The Path to National Suicide

Two and a half years ago, while we were driving in his car on Long Island, I told my friend Dean Ericson the story you are about to read. He strongly urged me to write it up. I agreed that I should do so, but the physical difficulty I have in writing anything longer than a short blog entry or a comment led me to delay it all this time. Last month when Dean was visiting me where I am residing now in Pennsylvania, he brought a video-audio recorder and asked me, or rather he told me, to tell the story again. So we sat down in the living room and I began talking. I was pretty weak that day, and it took an effort to speak at such length, but I did it. It was a good idea, because I very well would not have written it on my own. Dean then transcribed the recording and sent me the text. I’ve edited it to make it read more smoothly, to fill out a couple of ideas, and to add a couple of points I missed during the interview. The Path to National Suicide: An Essay on Immigration and Multiculturalism is not currently in print, but it is available free online, in both pdf and html versions, at the Lawrence Auster Unofficial Page which contains my non-VFR writings.

However, there were some signs that I was bothered by the diversity. The first time I became consciously aware of it was when I visited Aspen in the summer of 1980. As I was walking down the street I realized how peaceful and calm I felt, and I realized that the reason was that Aspen was all white. There were no blacks or Hispanics. I suddenly became aware that I had been experiencing a constant, low-level tension in New York. Also, around this time, around 1980-81, I had a very strange and disturbing dream. In the dream, New York City was suffering from a plague or a vermin infection, and a group of people including me had fled the city to the back yard of my parents’ home in South Orange, New Jersey. We were gathered there to escape the plague. Somehow it was understood in the dream that the plague signified the vast increase in the numbers of Third Worlders in New York, as well as blacks. However, insofar as Third-World immigrants were concerned, these were not thoughts that I focused on or worried about. My basically positive, or at least unworried, attitude toward diversity continued. (Blacks were another story; regarding the black underclass and the black activists, I remember thinking and saying to some people around this time, “The worst people who have ever lived on planet Earth are alive today in New York City.”) Then one day in 1982—I don’t know whether I was standing on a street corner or sitting at my desk in my apartment when this happened, nor do I remember what triggered the experience—but suddenly my paradigm shifted completely. Something made me realize, I don’t know what it was, but I grasped that what I had interpreted as a harmless, benevolent, fun, interesting sprinkling of different kinds of people at the margins of our society, was in fact going to displace white America. Was going to displace and push aside the white race, was ultimately going to eliminate the white race as an autonomous force in history and eliminate white Western civilization, not just in New York City or in America but as a totality. I saw all this in a single instant. I saw the white race being pushed aside in America and in all the white countries. And what this meant to me was the destruction of everything we were, everything we had been, everything we had, all our past, the civilization that we have inherited, our history, art, culture, it was all going to be pushed aside and destroyed. I literally saw this and felt it in a moment of time. I was overcome with horror. It was the greatest horror I have ever felt. It’s frustrating that I do not remember what exactly set off this insight. At that period I kept personal journals, but I have not been able to find a journal entry on this. DE: Did you have any idea, at the time, of what was driving it? LA: I don’t remember what my understanding was of why this racial transformation was taking place. I’m sure I had some understanding of it but I don’t remember what it was. How much was I aware of immigration at that moment? I don’t remember. Certainly I became aware of the immigration issue very shortly thereafter. But what I do remember of it at the time was just as I described: The white race is doomed by the ever-increasing number of nonwhites in our society. Everything we have, everything we esteem, everything we are, is going to be pushed aside and wiped out. DE: And yet you did not write about it at the time? LA: No. I thought about it a lot, I became deeply preoccupied with the subject. For example, I noticed how, in various parts of the city, especially the subways, the scene was foreign and alien. People who did not have anything in common with America were dominating the scene, and my obsessive, burning thought was, “What are they doing here? Why are they here? Why are we allowing them to be here? And why don’t we care?” Sometimes I would look at other white people in a subway car that was dominated by nonwhites and I would say to myself, “Don’t they see this? Doesn’t this bother them? We had a white country, now it’s becoming a nonwhite country and it doesn’t seem to bother anyone. It doesn’t strike anybody at least as being strange? It’s just ordinary and to be taken for granted? Or not even taken for granted, just not noticed at all.” That bothered me and I began to think about what could be done about this. I had this notion that there’d be other people, whom I called in my mind “the big people,” who would have to take care of this problem. So, for example, in the mid-eighties I saw a PBS program hosted by Bill Moyers about the problem of bilingualism and I thought, “Well, if he understands that bilingualism is a problem then maybe he’d be sympathetic with my concern about immigration.” I wrote him a letter, isn’t that silly? I wrote the ultra liberal Bill Moyers a letter about the problem of non-white immigration! But I was searching. There had to be someone out there, among the “big people” who influence and run society, who determined opinion. If anybody’s going to turn this around they’re the ones who will have to do it. That was my thinking. But I realized pretty soon that there was no one who was noticing or criticizing this. There were various articles about immigration and the increasing diversity in America but they just basically said, even the strongest said, “Hey, our society’s changing, it’s getting diverse, but it’s fine, it’s interesting, it’s okay.” DE: You never thought that your perception might be out of place? Your thought that you saw the entire white race being pushed aside, you didn’t question that and think, well, maybe I’m just over-reacting? LA: It was not being pushed aside at that moment, of course, but I saw that that’s where things were heading. That was a certainty in my mind. That was the ultimate direction of these things. Then I also began to research immigration. I found out about the 1965 Immigration Reform Act. I went down to the main building of the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue and 42nd Street and I found the transcript of the Senate Immigration Subcommittee in 1965 of their hearings on the 1965 Immigration Reform Act chaired by Edward Kennedy. I spent many hours at the library reading this large hardcover volume with the committee transcripts. I took a lot of notes on it. DE: Did you have an idea of writing about it or was this just to satisfy a curiosity? LA: I don’t remember. I was studying it, I was taking notes, I was learning about it. I was probably thinking about writing about it. Reading the committee hearings, the things that were said then (which I later discussed in detail in the first chapter of The Path to National Suicide) was a huge eye opener. So at that point I began to think more and more, well, I have to write about this. But I absolutely hated the thought of writing about it. The subject was extremely traumatic, extremely disturbing to me. I did not like thinking about it. I did not like thinking about what would be coming. It was too upsetting. Also, I felt that it would be wrong. I’d be opposing something that everybody felt was right and I’d be seen as a hater. Adding to my difficulties at this time was the fact that I had no conservative intellectual friends or associates at all. I knew no one who even remotely shared my ideas about immigration. In developing my views, I was totally alone. To give the context of the next part of the story I have to go into another aspect of my life. During the period I’m discussing, I was briefly a follower of the Indian spiritual master and self-described “Avatar of the Age” Meher Baba, who passed away, or “dropped the body” as he put it, in 1969. Avatar means incarnation of God. I had been interested in Baba from about age 21 and regularly read his works, along with other spiritual and religious teachings including the Gospels, the Gurdjieff-Ouspensky work, and the writings of J. Krishnamurti, In 1987 I became more serious about Baba and was a Meher Baba follower from 1987 to 1989. (In 1989 I became a Christian believer, and in 1998 I was baptized at St. Thomas Episcopal Church in New York City, an Anglo-Catholic parish. I felt then and still feel that my involvement with Meher Baba had made it possible for me to become a Christian; that I could not have become a Christian by a more conventional route; and that the role of Meher Baba in my life had been to lead me to Christianity. But that’s a whole other story, which I also want to tell at some point.) The headquarters of Baba and his followers in the West is the Meher Spiritual Center in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. I visited the Center three times for a week, in May 1987, May 1988, and May ‘89. Also in the summer of 1987, a month after I first visited the Meher Spiritual Center, I went to India and spent three weeks at Meherabad, which had been Baba’s headquarters while he was alive and was and is still the headquarters of his followers. It is where Baba’s tomb is located. In 1987 and 1989 I drove to Myrtle Beach; in 1988 I went by plane. In early June 1988, I had flown back from Myrtle Beach to Newark Airport and was riding back to Manhattan in an airport bus. I’m in this spiritual mood having spent a week at the Meher Spiritual Center. Most of the passengers on this small airport bus were East Asian people, Asian men, probably Chinese. Initially I had my usual thoughts of, oh, here we go again, we’re being taken over by nonwhites, but that passed, because I was in a more peaceful, spiritual state. It was maybe 10 o’clock at night, and I went into a kind of reverie, a daydream. And in this reverie I was thinking that I and these Chinese people were connected by love. That they loved me, and I loved them. There was no problem between us. The ultimate reality was unity—that, as human beings, we were one. We were spiritually one. There was no conflict, no division. The ultimate truth was oneness and love. But here is where something very strange happened. You would think that what I’ve just said would lead me to a liberal, globalist epiphany: we’re all one, there’s one world, one humanity, there should be no borders, no separate nations , no separate races. Of course that’s what Baba followers typically believe. Instead, this is what happened to me. From this experience or glimpse or daydream of ultimate unity and love, I realized that I did not hate anyone. So hatred and fear, at the deepest level—or not even hatred but the fear of hatred, the fear of me hating other people—was gone. It was removed from me. Not only that, but it never came back afterwards. And I believed that this experience had come to me from Meher Baba, or from God. It was a gift from God. As a result of this, I saw two very different things at the same time. First, at the ultimate level of reality there is love and oneness; but, second, humanity is not living at the ultimate level at the present time. We are human beings living in the actual world. A world of separate countries, civilizations, peoples, cultures, and the differences between them matter. Matter practically, matter profoundly. So, ironically, my experience or reverie of spiritual love freed me from the fear that my discriminatory or exclusivist beliefs were hateful. The net result of this experience was that I lost what had been the paralyzing fear of my being a hater, which had kept me from starting to write up the ideas on immigration I had been developing. Up to that moment, I had dreaded the idea of engaging seriously with these ideas, of writing them and publishing them. That fear and that trauma were removed from me. And they have never returned. Ever since that night I have never been afraid of being called a racist. And I have never been afraid of being a racist. I feel that this experience was given to me by—however you want to put it—Meher Baba, who was a spiritual master who said he was one with God, or by God himself. In any case I have always believed that it came from God. It delivered me. But—supreme irony—it delivered me to become, not a liberal globalist, but the complete opposite of that. And from that deliverance I began to write, in June 1988, the notes and fragments that grew into The Path to National Suicide, though I only started serious work on the project in February 1989. At that point in time, other than undergraduate papers, some very long and ambitious, that I had written when I went back to college at age 27 and got a B.A. as an English major, I was not a writer at that point, though I had written a few articles for small New York newspapers. I didn’t become a writer because I said to myself, “I want to be writer.” I was compelled to start writing, against my will, because of my passionate concern about immigration and the threat it posed to white civilization. But writing PNS was the beginning of my career as a writer. Of course other people cannot have my exact experience. But they can understand the principle of my experience, which could liberate them as I was liberated. And I say that the reason why whites—even whites who are deeply concerned by the demographic, racial, and cultural changes taking place in our country—are still paralyzed and incapable of doing anything about it or speaking out against it is that, in addition to the fear of social and professional ostracism, they sincerely feel that to take such a position would be wrong. They feel it would be racist. Meaning that if they have or state these views that means that they hate other people, which is morally wrong. But if you experience, in some sense, humanity’s oneness, and at the same time you grasp humanity’s actual differences in the present order of things, you see those two truths at the same time. You’ll see the harmony on one level, the absence of hatred, our beautiful (potential) oneness as human beings, and on another level you’ll see the legitimacy of distinct societies, distinct peoples, and the need to protect and preserve them. But without hatred of others. This is not rocket science. To say that on one level mankind is one, and that on another level mankind is divided by differences, is not rocket science. But for people today it does seem to be rocket science. They can’t grasp it. Contemporary people living under liberalism have two idiot alternatives: either we’re liberal globalists or we’re Nazis. That’s the total universe of possibilities for modern liberal Westerners. And that limited view is killing us. Americans and other Westerners have to break out of that simplistic and false way of thinking and realize that the consciousness of differences, the desire to preserve our own distinctness, our uniqueness, is perfectly legitimate and moral. Most race-conscious whites who have not had any glimpse of unity—and in most cases they’re not religious at all but materialist racial reductionists—they do believe that they hate other people. That’s why so many race-conscious whites—paleocons, white nationalists and so on—positively affirm; “I’m a racist.” Since liberalism says that their view is racist, they affirm that it is. They say, “We’re racists. I’m a racist.” That’s nowhere. That can go nowhere. Especially for Americans. Americans have to believe that what they stand on is morally right, is based in moral principle. People who proudly call themselves racists, or who call themselves “tribalists” as most paleocons do, are not basing themselves on any larger moral principle. They’re just basing themselves on “us versus them.” Of course on a certain level there is “us versus them,” but that is not the ultimate reality. The “us versus them” has to be in a larger moral and civilizational context, a context that helps determine which types of feelings toward “them” are okay and which types of feeling toward “them” are not okay. But the paleocons who call themselves tribalists do not have such a moral framework. So the liberals are screwed up in believing that only global oneness is moral, and the tribalists and paleocons and white nationalists are screwed up in thinking that only tribalism is real. I have always felt completely unafraid of taking the most political incorrect, anti-liberal positions. Why am I so unafraid? I think that at bottom it’s because I know that I’m not a hater. I know that my position is based on moral and civilizational truth, not on anger or nastiness or hatred. And that’s why I, in my own way, as a writer, can stand completely against the liberal views that all of society, including conservatives, holds, the belief that any consciousness of race and its importance is morally wicked. I know that it’s not wicked. I know that race and race differences are true, they are part of the truth, and they are an important part of the truth, along with other truths about mankind. In February 1989 I began writing it seriously. I had enough money that I didn’t need to work to earn a living for a few months. I completed the first draft in late May 1989, just a few days before my annual trip to the Meher Spiritual Center, and sent it to American Immigration Control Foundation, the only organization opposing our immigration policies on a cultural basis. They had published several very worthwhile pamphlets on immigration, though not addressing race itself, which was the central issue for me. Palmer Stacy, the then president of AICF, got right back to me. He left a message on my answering machine, maybe two days before I left for Myrtle Beach, in which he praised the manuscript highly and told me he wanted to publish it. That was extremely encouraging. But I told him the manuscript was nowhere near a publishable state. It was a first draft. I had sent it to them to get a response, to hear what they thought of it, to get encouragement, not to publish it. So I continued working on it through several drafts and then the galleys—at every stage it was extremely hard work—until it was published by AICF in December 1990. They had given me complete latitude. Every word, every comma, even the typeface, was determined solely by me, though I had also given the manuscript to various associates to get their criticism and suggestions, some of which were very important to the final outcome. For example, in the first draft I had blamed only liberals for the immigration disaster. One person from whom I sought feedback was the late Ed Levy, a liberal New York musician and music teacher who was on the board of advisors of the Federation for American Reform (FAIR had started out as liberal population-control organization) and who lived literally around the corner from me in New York City. When we got together at his apartment to discuss the draft, Ed pointed out to me inter alia that conservatives were a part of the immigration disaster as much s liberals. That was a very important insight for me, and I changed the manuscript accordingly, which significantly improved it. Also, almost every person who read the draft (other than AICF as I recall) forcefully told me that “The Path to National Suicide” was not an acceptable title, as it was too grim and extreme and would repel people. I took the criticism seriously, and over many months I kept experimenting with other titles. But I rejected them all. Finally I had a clear realization that “The Path to National Suicide” was, notwithstanding the problems it presented, the right title for this book, that it was destined to be the title, and I stayed with it despite the continued strong disapproval of virtually everyone who had read the manuscript.

Paul K. writes:

This is a wonderful article. I’m so glad you got it down in writing. Like your essay “Racial Differences in Intelligence: The Evolution of One Person’s Views,” it leads the reader through the thought processes of a reasonable and perceptive man. The personal element makes it easier for the reader to identify with you and understand your ideas than would be the case if you took a more impersonal or journalistic approach.Felicie C. writes:

You write: “A world of separate countries, civilizations, peoples, cultures, and the differences between them matter. Matter practically, matter profoundly.”LA replies:

This is very well stated and I agree with you. But I quibble with your use of the concept of entropy. Entropy is a mechanical process relating to physical phenomena. It is not an appropriate concept when we speak of the realm of human meaning, of human civilization. It is commonly used as a metaphor for mental, spiritual, and cultural phenomena. But it’s wrong to make a mechanical, physical process a metaphor for phenomena which are not mechanical, but involve human thought and human choice.Rick Darby writes:

Your latest posting is one of your best and most unusual, so I’d like to comment.LA writes:

The following comment by Mencius Moldbug is over 900 words long, but, unusual for his writings, it is reasonably cogent and fits together and I couldn’t see how to abridge it. So I’ve posted the whole thing.Mencius Moldbug writes:

Larry, I’ve said it before but I’ll say it again: You’re a goddamn genius.LA to Dean Ericson:

Today I’m in my usual very unusual state: totally wrecked by the radical four-week lack of sleep caused by the steroids, and also energized by the steroids. I got out of bed at 2 a.m. and worked two hours making more improvements in the interview, which were needed.Dean Ericson replies:

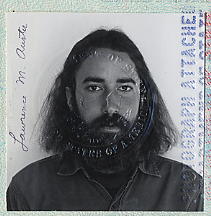

Great piece. Good you had the gas to pound it out. Especially picturesque is the image (I’m thinking of the 1973 passport photo) of a long-haired, 1960s, Meher Baba-following, Aspen-coffeehouse-hippie-sort-of-guy as the man who would eventually write The Path To National Suicide. At first glance it’s jarring. But looking deeper one sees the underlying harmony. Posted by Lawrence Auster at March 07, 2013 09:45 PM | Send Email entry |